As investors, we need to analyse the opportunity and derisk it before deciding to invest. This post takes a deeper dive into a assessing a development deal – it goes through the steps I undertake before making every investment decision. The content is relevant for both debt and equity investors but the return analysis is most relevant to the latter.

The post assumes you’ve already done due diligence on the property developer. If not, STOP! and begin with that critical first step of the derisking process. Remember, no matter how good a project looks, it’s only investible if executed by a competent developer. I have a separate post on how to assess developers which you can read here.

… and welcome back! Hopefully you have successfully derisked the developer. Now to the deal itself.

A recap of Debt v Equity

A property developer will look to raise capital from investors in either debt or equity format (sometimes both). It all depends on the developer’s needs, the availability of other sources of finance (eg banks) and investor appetite.

From an investor’s perspective: Equity returns are usually higher than debt (all else being the same). On the flip side, the equity return is not fixed: it can be higher than expected (if the project makes higher profits) but it could even be negative.

On debt the return is lower but is fixed, regardless of profits. Debt-holders get paid back before equity holders in the same project. The only time a debt investor loses money is if the value of their security falls below the investment amount.

Think of debt/equity in terms of your house. The mortgage provider owns the debt (fixed, lower return) and you own the equity.

From a developer’s perspective, the cost of debt (the rate paid to investors) is less than equity but has to be paid regardless of the level of profits made on the project – which could mean having to pay investors from personal capital (via a PG – Personal Guarantee). Equity is more costly for the developer but the advantage is that returns only need to be paid when there is a profit. Importantly, equity funding lets developers scale up their businesses by partnering up with investors with whom they can share their profits with.

In summary:

For developers: Equity costs more than Debt. But Equity is safer for the developer because there is no personal security involved.

Typical debt returns available to investors

Currently, typical debt returns are in the range of 6-18%, annualised. The range is wide because each deal has varying characteristics with the general rule being that return is related to risk (or perceived risk). Factors include:

- Leverage: a lower loan-to-value (LTV%) means lower risk, equating to lower returns. Conversely, a high LTV (75%+) is considered high risk and requires larger returns to compensate for the risk of a moderate market correction that might place investor capital at risk

- Security: the more robust the security is, the less is the risk so returns don’t need to be high. The best form of security is a first charge on the property (with low LTV). Other forms of security include second charge on the property or a formal Personal Guarantee (PG) on the developer’s own assets. These “junior” forms of security are more risky and require higher returns.

- Timeframes: a longer project means investors would require higher returns. There are no benchmarks because it depends on project size etc. Personally, I am cautious of durations greater than 18 months.

- Urgency of funds: a developer has to offer higher returns if capital is required urgently

- Reputation: higher quality developers are less risky so are able to raise capital with lower returns (our DD on developers helps us determine whether the reputation matches reality)

- Asset quality: the better the property (location, liquidity, future demand), the higher the probability of project success – meaning lower risk and lower rates

- Planning Permission: is the success of the project reliant on planning permission? If so, has the probability of success been derisked by pre-planning guidance and/or planning consultant advice? An investment reliant on planning permission (PP) has to return higher than a similar one which already has PP (see below for more on PP)

- Profitability: a higher expected development profit means a larger buffer, making investor capital safer. This can be made possible if the developer acquired the site at a below-market valuation. A great scheme design also results in higher profitability.

Typical Equity Returns available to investors

Equity returns have an even wider range than debt: 25-60%* is typical but we often see outliers as high as 100% and as low as 20%. Not only is the expected range wide, but the actual resulting return is variable depending on the resulting profits. When a developer advertises an equity return, it’s an expected return, based on final profits – not fixed like with debt investments.

* (These equity returns are after deducting the developer’s profit share (typically 50% of total profits) and are leveraged returns – i.e. the project has been funded with debt and equity).

For equity investments, the biggest factor driving your return is the level of profits the development makes. Clearly, higher profits means more money for investors. However, as an equity investor you must also note the debt risk factors listed above because they affect the riskiness of your expected profits.

Bottom Line: As investors, our job is to derisk every opportunity by: 1) being aware of the risks and 2) assessing and verifying the advertised return. How we do that follows.

The timeline that makes a successful investment …

Select a Competent Developer → Select the right Project to invest in → Successful Execution of Project → Net Profits → ROi → Equity Return

Specifically, Equity Return = ROi = Your share of net profits, divided by your invested capital

Example: the project makes net profits of £100k and your share of that was £10k (the developer receives 50% profit share). If your invested capital was £40k, your ROi is 25% (£10k divided by £40k).

We obviously know how much we invested but the key unknown – at the start – is the net profit expected from the development.

Expected Net Profit – the key to understanding your return.

A good developer will present you with a detailed appraisal and cashflow/P&L forecast on an excel spreadsheet that takes into account all possible cost and revenue items. This might amount to hundreds of line items ranging from property acquisition cost, legals, taxes, professional fees for planning, engineering, design, construction costs (if the project is a build-out), financing costs (payment of interest on debt) – and all the way through to selling costs at the end. And the all important revenue item(s): property sales and, possibly, the disposal of the freehold.

As investors, our job is not to go through each item, line by line. We rely on our competent developer to have done that. Remember, we have done our DD on the developer’s track record/competence. And they will have invested in professional – and independent – analysis from Quantity Surveyors (QS), planning consultants and architects for optimising scheme designs.

After this, our job as an investor is to verify the headline numbers in the appraisal and the assumptions used – and then stress test the developer’s numbers. To do this properly, below are 10 critical factors that need to be evaluated.

The 10 Factors That Will Determine Your Return

1. Gross Development Value (GDV)

– Is it correct? Have all exit strategies been considered?

GDV is the money the development brings in – or the revenues. It’s the largest component of the appraisal and one that swings around the most. So it needs the most care and risk management.

On residential schemes we are likely to see one of four GDV scenarios, or exit strategies:

- Build Out: The completed scheme, post Planning Permission (PP) and build-out. Units to be sold individually

- Planning Uplift: The site with approved planning permission, but not built out (“Planning Uplift”) The whole site to be sold to another developer to build out

- Enhanced site without PP: The site with enhancements made not requiring full PP, then sold on

- Build-to-Rent: Rather than sell the units, rent out to tenants

Build-out GDV

Here, GDV is the sum of all the selling prices of all individual units in our completely developed scheme.

Derive the current market value of each unit using comparables, sold prices and local agent intelligence. We can also repeat the exercise used above (in point 1. Acquisition Cost). Except, you’d do the valuation for the completed not purchased scheme. Things to be particularly careful about:

- Can the scheme be absorbed into the local market? (esp if it’s a particularly large scheme). It’s one thing to value the GDV using the sum of all the market values for each unit. But can they be sold? That depends on how liquid the local market is and how well the units can be absorbed. For instance, if the local market normally sees 5 transactions per month, a new development of 75 units may take a while to be absorbed into the market – almost rendering the theoretical GDV meaningless.

- Only use today’s market values. Some developers bake in an increase in market prices into the GDV, thereby flattering it. For instance, the current comparable of a 2-bed flat in the scheme is £250k but the developer values it at £270k in the GDV. If you see this, make your own adjustment to the GDV by only assuming today’s value. I might even discount by 5% for larger developments.

Planning Uplift GDV

Here, GDV is the price we sell the site to another developer for.

If the strategy is to obtain PP and sell the site, we still need to go through the GDV process, as though it was being built out. This is because we need to place ourselves in the shoes of the buyer of our site. Our buyer will estimate GDV on a completed basis so if we do the same thing, we can work out the price they’d be willing to pay – i.e. their buying price is our GDV.

⇒ At InvestLikeAPro we prefer the planning uplift strategy for various reasons, including better overall returns and more effective risk mitigation. And all it takes is one (overly optimistic!) developer to buy your site at a fantastic price.

Enhanced Site (without PP)

This might be a stand-alone strategy or a “Plan B or Plan C” where intended PP has been refused.

The GDV in this scenario is the value of the property/site after carrying out some kind of enhancement which doesn’t require full planning permission – Eg an internal refurb or an extension that can be done on a “Permitted Development” (PD) basis.

Build-to-Rent (BTR)

GDV would be the final valuation of the completed properties. Capital return would be possible through a refinancing of the rented properties.

Compared to the strategies listed above BTR does not have as clean an exit – especially for equity investors, for whom a clean exit means receiving capital and profits without holding a continuing interest in the project.

BTR can be employed as a strategy if a profitable exit cannot be made. This might be the case if the market suffers an unexpected correction prior to an intended sale. In this case, the rental market may still be good, enabling a refinancing opportunity to return some capital back to investors, with the rest being tied up in the properties.

2. Acquisition Price – did the developer get a good deal?

The developer must have already negotiated the buying price of the property/site – whether this is an outright purchase or conditional on planning, or an option-to-buy.

Was it a good price? Look at comparable properties on the market. Look at sold prices of comparables. Ask a few local agents for their assessment. Be sure to compare like-for-like:

- For residential sites, look for similar plot sizes, location and recently marketed/sold data

- For commercial sites, we value using a multiple of rental income. Check what is the correct multiple to use for that type of property and in that area – the multiple differs across sectors and locations – it could range from 5x for a retail site in a lower tier city to 20x for prime office space in central London

- For unused land, the valuation gets trickier but we use a residual land value method

The main point of this exercise, for investors, is to have an idea what the asset is worth on the open market (OMV), post purchase. If planning does not succeed, or further development is not carried out, is the existing-use OMV high enough to recoup the acquisition cost?

(there are times when an above-market price is negotiated – eg a conditional-on-planning purchase. This is usually not a problem because the above-market price is only paid when there is a planning uplift in valuation).

3. Planning Permission (PP) – important to derisk before investing

If the expected return assumes PP will be granted, investors need to assess that likelihood. We need to derisk by asking the following:

- Has the developer engaged a good (independent) planning consultant to advise on PP? (a regular architect will not be sufficient for a large scheme application). A good planning consultant will assess the likelihood of PP.

- Another way to derisk is pre planning guidance from the local authority. If this was obtained, was it supportive? Ask the developer to send you the report

- Search the planning portals for any similar approvals in the area. Has local precedence been set for this type of proposal?

- As investors, we also need to have a worst-case-scenario (WCS) in mind. If PP is refused, what can be done with the site?

- Re-submit with an alternative scheme?

- Appeal?

- If an existing building, can it be enhanced without PP and re-sold for a profit?

- We need to re-work the valuations with each of these scenarios and see if the deal still stacks

4. Is there a Plan B (and C and D) for an EXIT STRATEGY?

Plan A sometimes doesn’t work out. Good risk management needs a Plan B, C or even D. Do they exist and do they still make money in your deal?

⇒ At InvestLikeAPro we invested in a planning uplift opportunity to secure PP for 7 new houses on a site, which expected to generate good returns. In derisking the investment, we laid out various scenarios to know our risks:

- Plan A: secure PP for 7 new houses

- Plan B: resubmit for 5 houses if Plan A failed

- Plan C: in case of a second refusal, carry out a rear extension (on PD) and a full internal refurb. This scenario would still have generated positive returns.

- Plan D: Rent out, in case the resale market became soft

In the end, we managed to get full planning with Plan A coming to fruition. The point of this scenario testing exercise was to derisk the investment by asking ourselves: What if PP was refused twice – can we still avoid losing money? Because the answer was YES, the investment decision was easier.

5. Professional Fees – have they been included?

These are fees paid for legals, planning advice and application, architectural design and scheme optimisation, engineering fees, ecological and structural surveys etc. Some fees are very case-specific, some are necessary/statutory, and a competent developer will know what to spend and what not to. As an investor, you should check all of these costs are included as part of the appraisal and net profits (and ROi) figure. A (very) rough rule of thumb is they amount to around 15-20% of build costs.

And don’t forget stamp duty (SDLT). There are handy online calculators that tell you the correct amount. Check the developer has included SDLT in the appraisal.

Finally, and particularly relevant for commercial sites, check if VAT has been included in the appraisal. Even though VAT may be reclaimable at the back end of the project, it still poses an initial cashflow consideration and must be in the appraisal, if applicable. If it’s not there, ask the developer why not (some sites may be zero-rated).

6. Construction Costs – professionally costed out?

If this will be a build-out project, we need to get a good handle on likely construction costs. Even with a planning uplift investment, we still need to estimate build costs because this dictates the selling price of the site with planning.

- First, ensure the developer has appointed an independent Quantity Surveyor (QS) to do a full and accurate costing of the intending construction. A QS costs money but their job is to cost out every single item required, down to the number of nails and bricks. Far better to invest in a QS than to get a nasty shock in material costs.

«It would be very unwise to invest in a project NOT costed out by a QS »

- Second, ensure the QS has costed out the very same project that is being planned for. For example, if it’s a 12-unit high-end project, make sure the QS report is not for a 8-unit standard-finish scheme! (this is not uncommon).

- Third, do your own sanity checks to see if you agree with the costings. Very rough rules of thumb can help for this stage – such as knowing the £/sqft construction costs for similar projects in the local area.

- Finally, ensure the developer has put in a contingency in case of cost over-runs. 10% of estimated costs is prudent.

Separately, we stress test cost hikes.

7. Section 106 and CIL – fully accounted for?

Local authorities also want a piece of the pie! The main ways are through Section 106 and CIL (community infrastructure levy) payments from the developer. Both impose a cost to the development. Check they are in the appraisal.

Section 106 is usually related to affordable housing. A development scheme of 10 or more units is normally required to include a percentage of units as affordable – i.e. they must be sold on at a discounted price, not at market price. The actual percent of units and the level of discount varies and may be negotiable with the local authority.

CIL provides for a financial contribution to the local authority to support local infrastructure. The amount of CIL is more transparent, with a formulaic calculation to determine the payment taking the form of £/square foot of new dwellings.

8. Are finance costs included?

The purchase of a site can be funded with debt and equity. The good thing about raising debt is that equity investors get leverage – i.e. equity returns are magnified. On the other hand, debt costs interest! Interest costs are a major component of the appraisal and the full costs must be factored into the appraisal.

Debt costs are likely to be incurred at two stages:

- At acquisition of the site. A site bought to be developed might get bridging finance to fund around 70% (LTV) of the purchase price, with 30% being funded by equity finance. In recent years liquidity has flooded into the bridging finance space, bringing down borrow rates to historically low levels. Headline rates fell to as low as between 0.6%-1% per month (other costs eg entry/exit fees of 1-2% are also payable). For a planning uplift or refurb project, the bridging loan is repaid at the sale of the site. For a build-out project, development finance may be obtained.

- Development finance can be raised for the build-out phase. This borrowing tends to be cheaper than bridging finance (typically below 10% pa).

As investors we need to verify that finance costs are reflected correctly in the developer’s appraisal. Ensure the right interest rates have been used (including associated entry/exit costs) for the right period of time. A 12-month project should reflect 12 months of interest payments at the agreed rate + entry and exit costs (1-2% of borrowed).

Separately, below, we stress-test finance costs for an over-run in timeframes.

9. Now Stress Test the main variables: GDV, Costs, Timeframes

Stress testing the net profits (ROi) is a very important exercise for investors. It tells us what would happen to our return if things don’t go to plan. Many developers don’t do adequate stress testing and, even if they did, investors should do their own.

A decision to invest should be made after your stress testing reveals safety

- Stress test GDV: Assume market prices fall 10% from today’s levels

- Stress test Construction Costs: Assume costs increase 15% from initial expectations

- Stress test Timeframes: Assume timeframes lengthen by 30% for a build-out and 50% for a planning uplift project

A lengthening increases costs, particularly bridging/finance costs. Timeframes get extended for various reasons: planning delays/refusals, construction delays or additional time on market for sale.

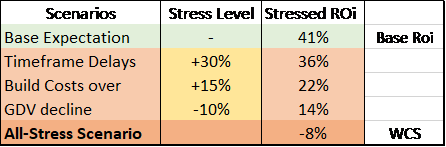

⇒ Below is a stress test InvestLikeAPro did on a recent project. It provided comfort that most of our stressed scenarios still made money. What gave more comfort was that the base expectation (returning 41%) already had conservative assumptions built in so our stressing was extra-harsh! The all-stress scenario – where all three variables are negatively impacted – results in a 8% loss. After going through this exercise (and all the other DD), we decided to invest.

As is evident from this table, the largest sensitivity on returns is GDV. Because it is the largest component of any appraisal, a change in GDV has a relatively large impact on investor returns. This is why investors should spend most of their DD time on GDV analysis. Test assumptions used, stress using your own findings and check absorption risks for larger schemes.

10. Has the investment vehicle been structured properly? (legal/accounting/tax)

A common and effective way to structure a development investment is a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). This allows multiple investors to participate and it has a legal structure that enables decisions to be made. The SPV should be administered by an accountant that is independent from the developer. Other aspects of the structure that investors need to consider:

- What is the profit share for the developer? 50% is typical and fair – if the developer is doing all the work and investors are truly passive. Is the profit share for the developer reflected in 50% equity or via a “consultancy fee”?

- Will the developer also be a director in the SPV? There are pros and cons with convenience one advantage and conflict of interests being a potential disadvantage.

- Will investors be individual directors in the SPV? If there are a handful of investors this should definitely be the case. If there are a large number of investors (via crowdfunding, for example), it would be more efficient to have one entity, as director, that represents all investors.

- When raising debt, will equity investors be asked to take on a PG? The preference would be for the developer to share in the PG

- There should be a shareholders agreement that lays out how the shareholders and developer will work together and how decisions will be made. This agreement needs to be checked by an independent solicitor and shareholders should be advised on its contents – and amended as necessary. The critical thing is for there to be balance between the developer and shareholders. The interests of both should be aligned in the shareholders agreement.

- How will investors invest? As individuals or via their Ltd companies? Tax may be a consideration here so get advice before investing

Join the InvestLikeAPro Investor Circle for free. You’ll be the first to receive new investment insights and helpful ideas on how to build your capital and invest like a pro. All in a risk-managed and diversified manner. Sign up at www.investlikeapro.co.uk

Manish Kataria CFA is a professional investor with 18 years’ experience in UK real estate and equity portfolio management. He has managed money for JPMorgan and other blue chip investment houses. Within real estate, he invests in and owns a range of UK property including developments, HMOs, serviced accommodation and BTLs.